SWA’s Annual Summer Student Program:

California Burning

We asked Sausalito Associate

Alison Ecker

for the story:

This summer, SWA’s annual Summer Student Program confronted one of today’s most critical climate change challenges: wildfire. As designers and planners of the built and natural environment, we are instrumental in protecting disaster-weary communities, helping sites to recover after wildfires, and designing new models for living in increasingly fire-prone landscapes. This year’s program investigated California’s escalating wildfire crisis in order to propose community-scaled design and planning solutions.

For 50 years, SWA’s Summer Student Program has engaged hundreds of students of landscape architecture, planning, and urban design from all over the world – many of whom have gone on to become prominent members of the firm and profession. Each year, the program takes on a topic of current and widespread significance and identifies a real-world site to research a relevant issue.

With the increasing intensity and frequency of wildfires worldwide, exploration of more resilient wildfire planning and design practices was a timely selection. As Northern California has become one of the unfortunate epicenters of this critical climate change challenge, the students gathered in SWA’s Sausalito studio for their initial four-week research studio before dispersing for a further four-to-eight-week internship at studios across the firm.

We spoke with Sausalito Associate Alison Ecker, this year’s primary program coordinator and a former Summer Student Program participant herself, to learn more.

Tell us about this year’s program participants.

We selected eight current graduate students from a large pool of 215 applicants. The students were chosen for their impressive applications, as well as for their ability to complement the skills and experiences of the entire group. All will be returning to their educational programs for the Fall 2022 semester.

Participants included Slide Kelly, MLA and Master of Design Studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Design; Luis Mota, MLA at the University of Southern California; Harrison Raine, Master of Environmental Planning and Master of City Planning at the University of California, Berkeley; Tejas Saiyya, Master of Urban Design at the University of Michigan; Yuanqing Su, MLA at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; Michele Totoy, Master of Sustainable Architecture & Landscape Design at Polytechnic University of Milan; Jin Zhang, Master of Urban & Regional Planning at University of California, Los Angeles; and Sydnie (Xinyi) Zhang, MLA student at University of Pennsylvania.

The students were joined by 13 teacher-practitioners from across SWA, who ranged from long-term principals to newly-hired designers, and included several program alumni. The entire Sausalito studio also supported the students in review and technical support. This is part of the firm’s long-term history and commitment to mentorship within the program and beyond. The structure is intended to create a shared knowledge-building environment: the students learned as much from the teachers as the teachers learned from the students.

What site was selected for study, and why?

We chose the 945-acre Sonoma Developmental Center (SDC) as our site for investigation. It’s located about 40 miles north of SWA’s Sausalito office in Sonoma Valley. The campus dates back to 1891, and served as a resource and refuge for those with developmental disabilities until its closure in 2018. In 2020, the State of California partnered with Sonoma County to envision a new future for the site and its surrounding landscapes. The outcome will be a Specific Plan that creates a framework for much-needed affordable and market-rate housing for Sonoma and a plan for the site’s open space.

The site offered a wide spectrum of conditions and contexts for the students to explore. The main campus center included a variety of buildings—now almost entirely empty—that were once used as housing, schools, stores, barns, and more. The surrounding open space included recreational fields and trails as well as well as agricultural pastures and gardens. Two reservoirs provide on-site water needs. The more natural areas are characterized by a mix of riparian corridors, grassy oak woodlands, and conifer pine forests. In many ways, the site is a small city unto itself!

The SDC is also no stranger to wildfire – in October 2017, a significant portion of its eastern half burned during the Nuns Fire. Although most of the buildings at the campus’ center were spared, it remains at risk. The vegetated areas remain thickly forested and mostly unmaintained, with ongoing drought conditions adding to fuel loads. The site is also susceptible to strong Diablo winds in the late fall, which increases fire risk.

With fire threatening any new development or redevelopment, the SDC campus and its context offered the ideal testing ground for the 2022 Summer Student Program participants’ study.

How was the study undertaken? What focal points emerged?

This year, each student developed a separate innovative wildfire proposal at the SDC site. The students’ resulting presentations demonstrated high-level thinking that both builds upon and challenges many assumptions about planning and design in a fire-prone climate. Taken in total, their ideas converged on four interrelated strategies.

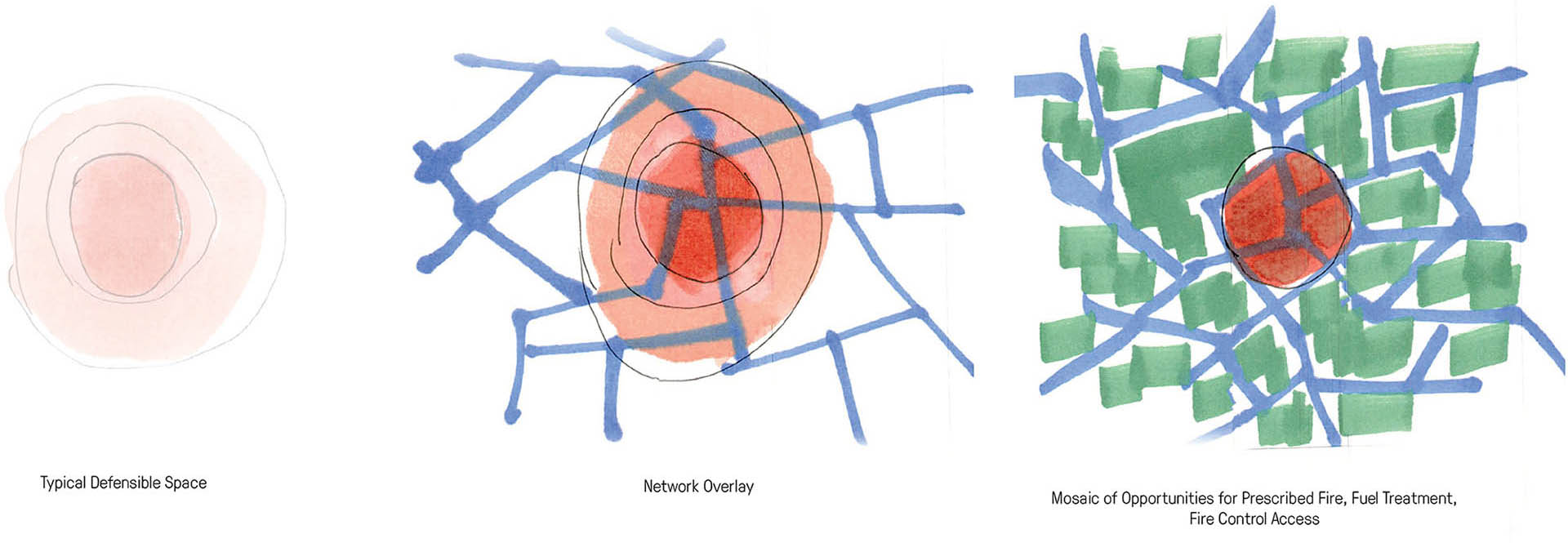

The first common strategy rescaled defensible space to the community level. While typical practices promote the concept of rings of maintained landscape around a single structure, the students proposed larger, collective buffers that protected the entire campus core. For example, one proposal created a large connected wetland, vineyard, and pasture as a buffer along the site’s eastern edge to disrupt potential fires moving from east to west across the site. Another proposed a large-scale, networked buffer approach, where the trail and roadway networks surrounding the core campus would form a mesh of protection.

The second common set of strategies presented dual-purpose concepts, with designs and plans that were highly livable, functional, and beautiful for everyday use, but simultaneously highly protective in the case of a wildfire. Some proposals showcased how trail and roadways systems could work to provide recreation and access for local users, while concurrently functioning as fire breaks and routes for evacuation in the case of wildfire. Another proposal introduced ways in which agroforestry practices could introduce a new economic opportunity for the site while also strategically clearing and thinning thick understory conditions.

The third main strategy derived from the fact that fire has been part of these particular landscapes’ natural history. Many of the students identified the need for controlled burns and successional landscape planning – emphasizing that not only is there such a thing as “good fire,” but that indigenous peoples made use of it long before the present day. Opportunities for education surrounding cultural burning and hands-on controlled-burn stewardship were part of these proposals, underpinned by the need to rethink communities’ relationship to fire.

Lastly, the students’ ideas examined development opportunities that would pair with projected popular uses for this desirable Northern California site with key fire mitigation goals. The area’s wine industry featured prominently, with tastings, tours, sales, and conferences validating expansion of fire-buffering vineyards and wine innovation centers. The reconsideration of development pattern density—with high-density but potentially easier to protect housing placed on the edge of the site—was also explored as an alternative approach to mitigating wildfire impact.